On Friday, I played my first concert in Miami in twenty-one years. Standing on the rooftop bar of Novotel in Brickell, waiting to perform, I couldn’t help but think of how I got from there to here and of the several lifetimes that have passed in between.

I went to college in Miami, started a band there, lived there, but I never fit there. Those were lonely years. I struggled to connect. I felt out of place and constricted and uncomfortable, like a giraffe in an elevator.

A stray memory of Miami: we received an offer to play a battle of the bands, the winner of which would open for the band Air. They had just done the Virgin Suicides soundtrack and MTV2 was playing the video for “Sexy Boy” a lot, so this was a big deal. We arrived at the venue—which turned out to be an Italian restaurant in an otherwise abandoned office park near the airport—and met the band. “I loved the Virgin Suicides soundtrack,” I said to one of them, a vaguely Cuban man who looked too old for his red pleather pants and platform shoes. “That’s A-I-R,” he said. “We’re H-E-I-R.”

It was, as they say, the oldest trick in the book. The old homonym shim-sham. That night, we played alongside a bunch of Latin death metal bands. The act before us ended their set by smashing their guitars over their amplifiers to a crowd of eleven people. We lost the battle, but perhaps we won the war.

Just before my final Miami gig in 2004, I decided to leave for Gainesville because I love Tom Petty and I thought Gainesville would be a better place to start a band. (It was.)

Over the next twenty years, I achieved almost every dream I ever dreamt. I made ten albums, toured the country a bunch, played Bonnaroo, had my music featured in film and television, and much more. But none of that was enough.

I never believe musicians who deny their lust for fame. It’s a cool thing to do, to seem above it all, but getting on a stage and saying look at me is an unnatural, even deranged act. It takes something stronger than the love of song to force a person up there. I started a band because I wanted to be as famous as the Beatles.

I spent roughly the first half of those twenty-one years in an ego-driven search for external validation, only to find that as soon as I reached the goalpost, it moved. My band stopped playing seriously in 2014—half the band had kids; I had started writing books; the sheen had worn off spending two weeks in a car to play for a few dozen people in Carbondale, Illinois—and I finally began to question this insatiable thirst. I spent the next years in a period of spiritual and personal introspection.

I went to therapy. I read philosophy. I became interested in the Stoics, like Seneca and Marcus Aurelius. It came as a great comfort to read Aurelius’s diary, written while he was emperor of Rome. Even he felt the absurdity of this unscratchable itch:

“This mortal life is a little thing, lived in a little corner of the earth; and little, too, is the longest fame to come—dependent as it is on a succession of fast-perishing little men who have no knowledge even of their own selves, much less of one long dead and gone.”

It struck me that if the most powerful human on the planet wasn’t impressed by fame or accomplishments, then they really must be empty vessels. It’s easy to fall from that realiztion straight into nihilism, to decide that nothing matters because everyone dies and everything is forgotten. I dipped my toe in it. But I found a way out, albeit a hard one, through Albert Camus and the philosophy of Absurdism. Camus holds that we are all stuck in an absurd existence pitting the desire for meaning against the impossibility of finding it, like the tragic Greek hero Sisyphus, pushing a rock up a hill all day only to have it fall back to the bottom at night. Amidst such futility, Camus argues that love only makes the absurdity hurt more and religion is a cop out for cowards who can’t bear the weight of life. And yet, Camus sees in all of this a challenge to rage against the dying of the light, “a lucid invitation to live and to create, in the very midst of the desert.”

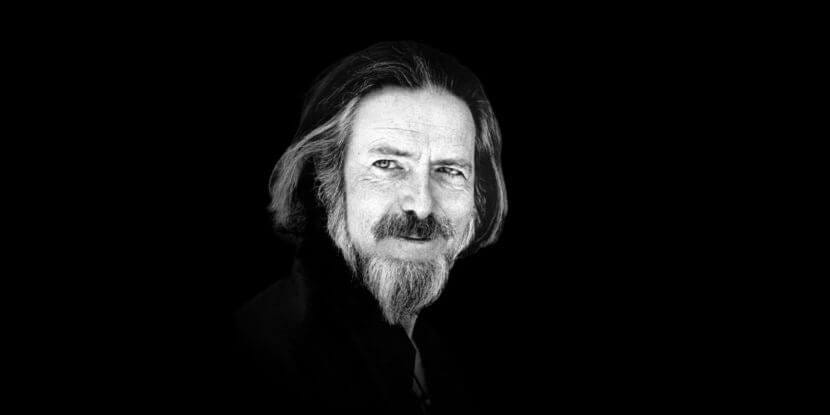

Ultimately, I found Absurdism too dour a philosophy. I read Suzuki’s Essays in Zen Buddhism and Alan Watt’s excellent The Way of Zen, and I found real comfort there. I liked the idea that to search for Nirvana is to miss it. It is not something one can attain. It is always already here. I liked the idea of living with “beginner’s mind.” I think that’s what Jesus meant when he said, “Unless one is born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God.” I think the Christians got it all messed up. The kingdom of God, like Nirvana, is not something one can attain. It is always already here. The mind, however, is a planning, calculating, predicting machine, and it tends to blind us to the true flow of life. Age, experience, and pain keep us in the past or the future. Being born again, like beginner’s mind, is a way of stripping back the mind, in order to experience that flow the way we did as children—not naively, but in the full splendor of total presence. Call it what you will: Nirvana, the Kingdom of God, the Tao, whatever.

Put it this way: when I was a kid playing in the backyard, I wasn’t trying to get anything or anywhere. I was dancing with life itself, full immersed in Nirvana.

I experienced many similar moments in music, jamming with a group of friends, just making it up off the top of our heads, playing only to play, until we were like birds in murmuration, communicating with each other almost telepathically.

I slowly began to realize that this sort of connection was the point. In fact, it has been among the most meaningful experiences in my life. Don’t get me wrong, achievement can be satisfying, and I’m proud of my rap sheet, but I had been so focused on achievement, I didn’t realize this whole other thing was happening. I became part of a community. I got to make art and share it with people who became my friends and my family. I am still doing this after two decades. Aurelius was right: this mortal life is a little thing, lived in a little corner of the earth. But that kind of connection is big. Massive, in fact. That’s the Kingdom of Heaven right there.

Twenty-one years ago, I left Miami, desperate to get somewhere. Last week, I returned knowing I was always already there.

AMEN. That'll preach.

What an interesting article.